Rear Windows Screen

The camera pans across a courtyard bypassing windows, showing glimpses of life. The view is – counter-clockwise and in full circle – from a rear window. Our perspective changes as the camera dictates and as it completes the circle we enter through that rear window and land upon the sweaty forehead of a sleeping man. The thermostat reads ninety-plus degrees, a warning that a brutal day lies ahead. But the residents of the buildings that surround the courtyard start their daily routine just like any other day. A man shaves and listens to the radio, another man and woman rise from their makeshift bed on the fire escape, a young woman makes her breakfast and a bird is uncovered alerting it that morning has arrived.

The camera pans across a courtyard bypassing windows, showing glimpses of life. The view is – counter-clockwise and in full circle – from a rear window. Our perspective changes as the camera dictates and as it completes the circle we enter through that rear window and land upon the sweaty forehead of a sleeping man. The thermostat reads ninety-plus degrees, a warning that a brutal day lies ahead. But the residents of the buildings that surround the courtyard start their daily routine just like any other day. A man shaves and listens to the radio, another man and woman rise from their makeshift bed on the fire escape, a young woman makes her breakfast and a bird is uncovered alerting it that morning has arrived.

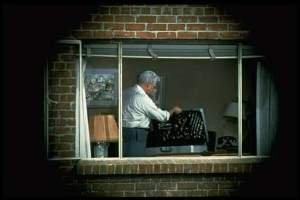

“Here lie the bones of L. B. Jeffries” says the leg cast on the man in the wheelchair as we enter through the rear window again. Then we move further into the room and pause on a smashed-up camera and up to photographs that depict violent car racing scenes frozen in time. We know immediately how L. B. Jeffries ended up incapacitated – he is a photographer used to taking necessary risks for his craft. We also know Jeffries’ world – as it is now – in relation to what surrounds him.

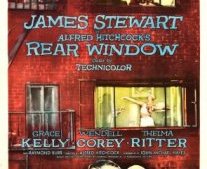

Without a word yet uttered we are completely acclimated to the setting and to the protagonist’s situation and have been introduced to nearly all of the characters through the rich, tightly woven tapestry that is Alfred Hitchcock’s, Rear Window (1954).

Without a word yet uttered we are completely acclimated to the setting and to the protagonist’s situation and have been introduced to nearly all of the characters through the rich, tightly woven tapestry that is Alfred Hitchcock’s, Rear Window (1954).

“The most unusual and intimate journey into human emotions ever filmed…revealing the privacy of a dozen lives!” – tagline

Based on a short story, originally titled, “It Had to be Murder” by Cornell Woolrich and screenplay by Michael Hayes, the central plot of Rear Window is simple – Unable to move about due to his broken leg, L. B. Jeffries is entertained by looking out his rear window into the lives of the people whose windows face his across a courtyard. Soon, however, what was a casual activity to quell boredom turns to obsession when Jeffries suspects one of the men across the courtyard has committed murder.

Soon, however, what was a casual activity to quell boredom turns to obsession when Jeffries suspects one of the men across the courtyard has committed murder.

“Nine out of ten (people) will stay and look.” – Alfred Hitchcock

The fact that L. B. Jeffries is enthralled by the lives of others is no surprise. After all, he didn’t have the internet or interesting blog posts to keep him entertained. That he should choose the apparent excitement of life outside his rear window as his preferred method of distraction is natural. His apartment is small and the windows are huge. The problem arises when he goes off the deep end and takes everyone else with him. And now I warn – spoilers lie ahead.

And now I warn – spoilers lie ahead.

Visiting Jeffries every day is Stella (Thelma Ritter), the nurse sent by his insurance company. Stella is the voice of reason, laying her “homespun philosophy” on Jeffries every chance she gets. And she smells trouble. Nothing good can come from looking out your window all the time. “What people ought to do is get outside their own house and look in for a change.” Stella offers comic relief in the story and judges harshly what Jeffries’ life has become, even if temporarily. Seemingly he is more concerned and/or interested in the happenings outside his rear window than with what is happening inside it. This is particularly true with regards to his love life, which takes the shape of Grace Kelly in the character of Lisa Fremont.